Magazine

Led By Donkeys — How four blokes with a ladder took on Brexit

They say that ‘strongmen’ leaders can stand anything — apart from being laughed at. And they say that the best way to win an argument is to quote your opponents' own words back at them.

Well, Will Rose, James Sadri, Oliver Knowles and Ben Stewart — better known as the (initially) anonymous Brexit ad-busting British guerilla outfit “Led By Donkeys” — certainly proved those two suppositions correct.

The four former environmental activists emerged out of nowhere in London (actually, out of an evening at an east London pub) at the height of the UK parliament paralysis caused by Britain’s 2016 wafer-thin shock referendum result (52 percent vs 48 percent) to leave the EU.

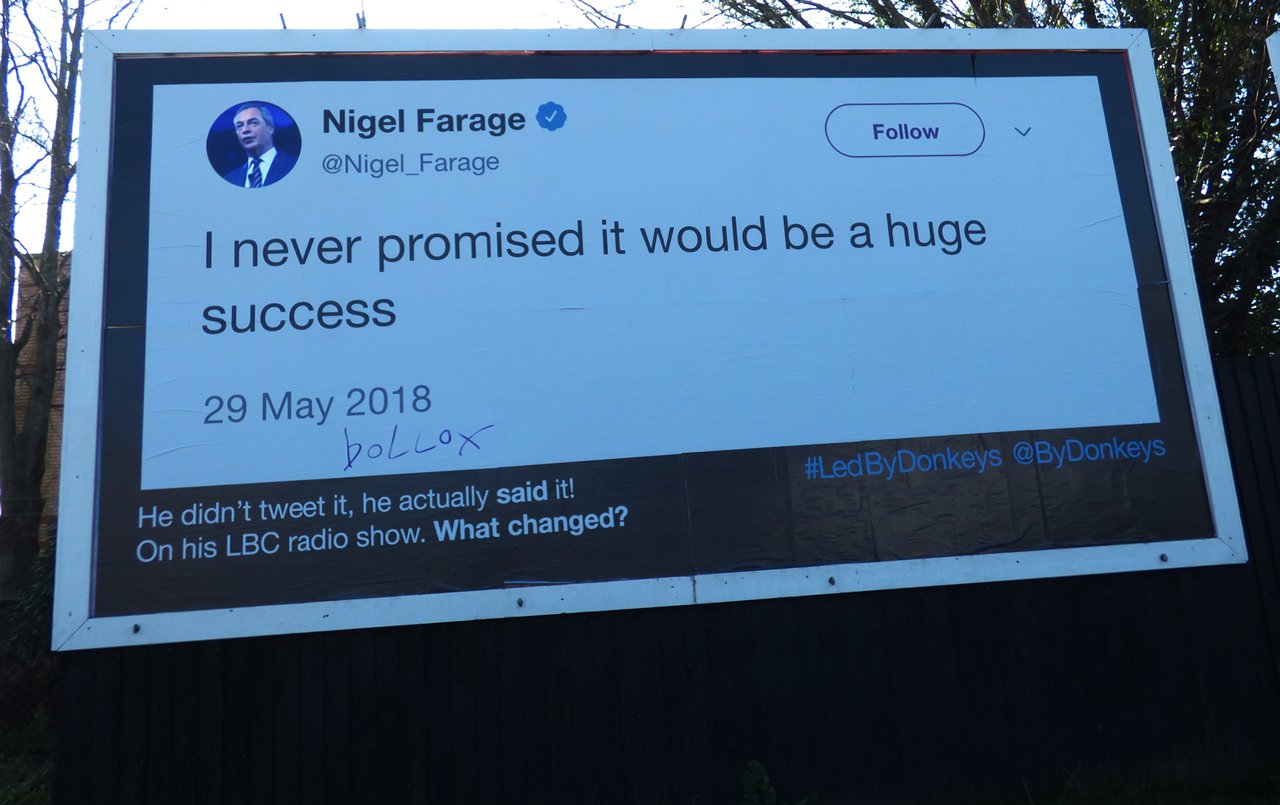

Armed only with a bucket of glue, a ladder, and presumably some torchlights (their work was done undercover, at night), the four ‘unsung heroes’ of the Remain camp plastered billboards across the capital, London, with blow-up images of tweets, campaign speeches and newspaper articles of the chief Leave protagonists’s failed promises (and lies).The main victims, really targets, were Nigel Farage (leader of the then UKIP party), Boris Johnson (then Conservative foreign secretary, plotting his route to Downing Street thanks to Brexit), Jacob Rees-Mogg (a Conservative MP who dresses and acts like a Victorian gentleman but is actually co-founder of a hedge fund), Dominic Cummings (the behind-the-scenes ‘brains’ of the ‘Leave’ campaign) and Dominic Raab (the Conservative Brexit minister who no one accused of being the ‘brains’ of anything after blurting out, two years after the Brexit vote, and whilst the actual Brexit minister, that he “hadn’t quite understood the full extent” of how much UK-EU trade depended on the Dover-Calais sea crossing).

That final quote, of course, soon became a meme after LedByDonkeys blew it up and put it clandestinely on advertising sites across London.

“Only after the [2016] referendum did it become clear that Brexit was a deregulation project; a threat to environmental regulations that we had fought for, a threat to workers’ rights and protections.”

But to rewind — the name Led By Donkeys (shortened to the hashtag #LedByDonkeys on social media campaigns), comes from a famous British saying about frontline soldiers during World War I being “Lions led by donkeys”, ie brave but disposable cannon fodder dying in the trenches of the Somme, while the generals were behind the frontlines, living it up in some commandeered chateau.

That was certainly the case with the 2016 Brexit referendum. Enraged by six years of so-called “austerity” cuts to British public services, which Farage skillfully blamed on the number of migrants in the UK, the voting public was sold the idea Brexit would be a “Take Back Control” moment. Plus the outright lie that Turkey was about to join the EU.

Instead of “take back control”, which was the public messaging, the true agenda was soon revealed, as Knowles told The Guardian in 2024 (after their identities were revealed).

“[Prior to Brexit] I definitely saw the EU as a distant power, very remote. It didn’t sit comfortably with my politics,” he admitted.

“Only after the [2016] referendum did it become clear that Brexit was a deregulation project; a threat to environmental regulations that we had fought for, a threat to workers’ rights and protections.”

The promises of “the easiest deal in history” and “of course we’ll remain in the single market” and “the German carmakers will be knocking on the door to give us a good deal” evaporated almost overnight, as from 2016 to 2021 the Conservative government hit parliamentary stalemate over how, and what sort, of Brexit it actually wanted.

Meanwhile, our four intrepid heroes were putting the original tweets of the victorious Leave camp on billboards at first across London, and later across the country.

For example, Nigel Farage in 2017 “If Brexit is a disaster, I will go and live abroad, I’ll go and live somewhere else”. (He didn’t.)

Boris Johnson, in February 2016, “Leaving would cause at least some businesses uncertainty, while embroiling the government for several years in a fiddly process of negotiating new agreements, so diverting energy from the real problems of this country.” (It did.)

Boris Johnson again, a year later in 2017: “There’s no plan for ‘No Deal’ because we’re going to get a great deal”. (We didn’t). Theresa May, the later Conservative prime minister who then pressed for the hardest-possible Brexit, in April 2016: “I believe it is clearly in our national interest to remain a member of the European Union”. (It was).

Rose, Sadri, Knowles and Stewart had previously been activists and environmentalists with groups such as Greenpeace and the League against Cruel Sports, and post-Brexit, have not stopped — although they’ve swapped the ladder and glue for video installations, and pop-up interventions, highlighting the hypocrisies of official government Covid memorials, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the child death toll in Gaza, among other hot-button topics.

Last year, they were back in the news for surreptitiously lowering an image of a cabbage, with the slogan “I Cashed The Economy” on stage behind Liz Truss, Britain’s shortest-lived prime minister, while she was on a pro-Trump speaking tour.

The cabbage is a reference to a tabloid newspaper live-streaming an image of a lettuce decaying, to see who would last longer during her disastrous September-October 2022 premiership. The lettuce won. The actually Remain-voting Truss managed a record-low 49 days as prime minister.)

Truss immediately stormed off stage, calling the stunt “not funny”. (It was funny). Rather proving the point that would-be ‘strong women’ leaders, as well as strong men, cannot bear being laughed at.

And do let us know if you're interested in a physical copy of the magazine here.

This year, we turn 25 and are looking for 2,500 new supporting members to take their stake in EU democracy. A functioning EU relies on a well-informed public – you.

Author Bio

Matthew is EUobserver's Opinion Editor. He joined EUobserver in June 2018. Previously he worked as a reporter for The Guardian in London, and as editor for AFP in Paris and DPA in Berlin.

Related articles

Tags

Author Bio

Matthew is EUobserver's Opinion Editor. He joined EUobserver in June 2018. Previously he worked as a reporter for The Guardian in London, and as editor for AFP in Paris and DPA in Berlin.