Feature

Freelance journalists in Europe: the costs of independence

Sara* is 43-years old and works as a freelancer in Italy. Like many of her colleagues, she regularly participates in European funding opportunities for journalism, such as JournalismFund Europe or Investigative Journalism for EU.

For freelancers in Italy, getting properly paid for investigative work — leaving aside all the legal risks — is virtually impossible.

"The real problem is that in order to be able to sell an article, you often have to neglect important topics and uncomfortable investigations because Italian newspapers don’t want them or are afraid of them, and you have to make pitches sexy for the daily news cycle... It’s this, above all, that impacts so much of our lives as freelancers as well as the Italian media landscape,” Sara said.

According to Eurostat data, in 2023, 868,700 people were employed in Europe as authors, journalists and linguists (all are included in the same statistical category): Germany leads with 237,600 people, followed by France with 92,800, then Spain (74,200), Italy (72,300) and Poland (69,600).

Italy, France and Spain provide an interesting starting point for a comparative reflection on the issues. There are also three countries for which the journalists involved in the Pulse project were able to collect testimonies and data.

In France, according to data from the Commission de la Carte d’Identité des Journalistes Professionnels (CCIJP, which issues press credentials each year), there were 34,444 professional journalists in 2023. The number corresponds to the number of press credentials issued and/or renewed.

In Italy, according to National Order of Journalists data, as of January 2024 there were 94,086 journalists registered with the organisation (of whom 26,086 are so-called “professionals”, i.e. those who exercise their profession continuously, and 68,000 are “publicists”, i.e. those who exercise their profession non-continuously).

'Let’s be clear: there are just under 100,000 members of the Order of Journalists, but there aren’t 100,000 jobs for journalists in Italy'

In Spain, on the other hand, there is no such official list. According to Eurostat data (which includes other professions), the sector employed 74,200 people in 2023, in a country with about 49 million inhabitants.

France has about 68 million inhabitants, Italy about 58 million. Italy has three times more journalists than France.

“Let’s be clear: there are just under 100,000 members of the Order of Journalists, but there aren’t 100,000 jobs for journalists in Italy,” says Alessandra Costante of the National Federation of the Italian Press (FNSI, the country’s largest journalist union, with 16,000 members in 2023). Given supply and demand, Costante said that “this dynamic is impoverishing the sector”.

In Italy and Spain, €50 for an article

“Not only is journalism in Italy getting poorer and older, but it is also more precarious. Precarity is the biggest muzzle on the freedom and independence of the media and on Article 21 of the constitution,” says Alessandra Costante.

Journalism in Italy is suffering. It is suffering from stress, it is suffering from precarity, and — as a consequence — it is suffering from a lack of quality.

The most comprehensive survey to date on the subject, with 558 participants, was published in IRPIMedia in 2023 by Alice Facchini.

“The factors that are identified as having the greatest impact on psychological wellbeing are first and foremost instability and precarity, followed by inadequate pay, always being connected and on call, and a frenetic pace,” Facchini says.

In Italy, six out of ten journalists earn less than €35,000 a year, writes La Via Libera. “Almost half of freelance journalists — who are often precarious collaborators or on VAT numbers — earn less than €5,000 a year, and 80 percent earn no more than €20,000”.

Alessandra Costante explains that the order once set minimum fees for self-employed professionals, but these were removed in 2007 after a request from the Competition and Market Authority. In 2014, a new agreement between FNSI and FIEG (Italian Federation of Newspaper Publishers) introduced minimum guarantees for freelance journalists, including pay, protections, and rights for those with ongoing collaboration contracts.

In fact, the pay rates in Italy are those decided by each media outlet.

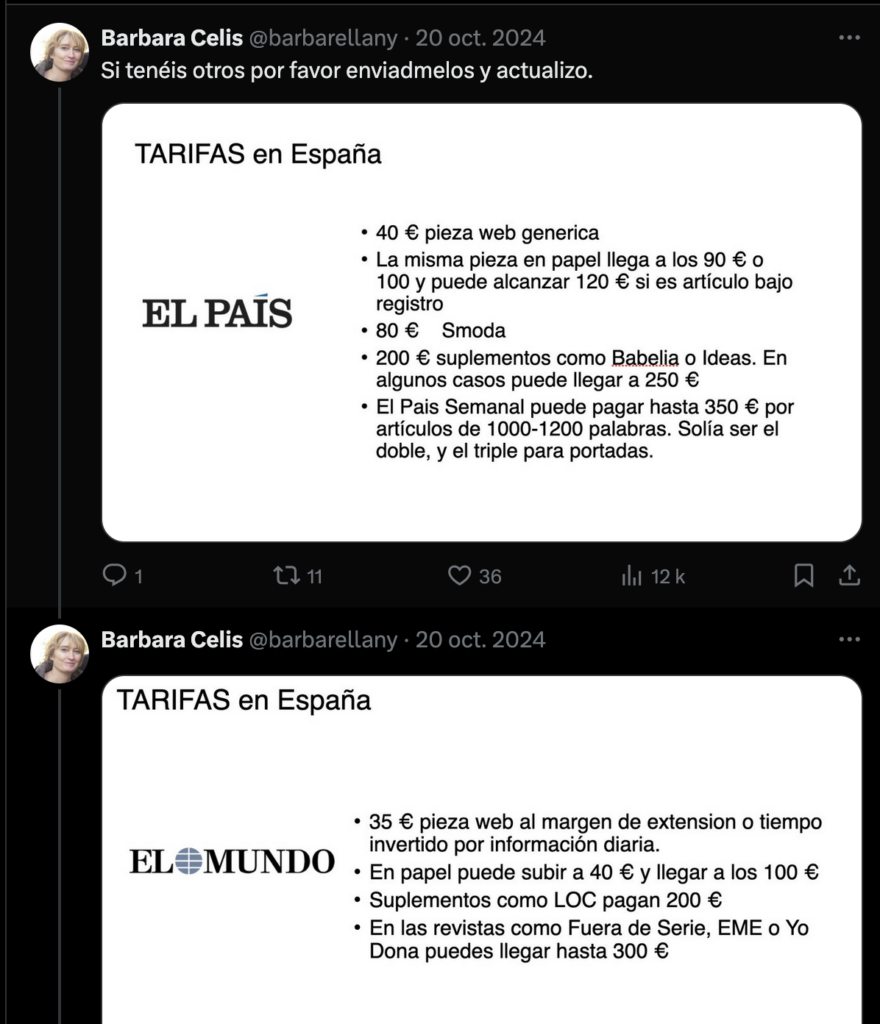

In Spain, the situation seems no better than in Italy, and the rates for freelancers appear to be similar. Some national newspapers pay between €35 and €40 per article, as this discussion on X indicates.

Esperanza* is 36 and has been working as a journalist for 11 years. “I haven’t found a Spanish media outlet that pays more than €100 per piece of reportage” she says, “no matter how much time you spend on it. Most pay between €50 and €70. For example, in 2016 I followed the refugee route in the Balkans, and a big media outlet paid me €70 for the report”.

According to figures from the Spanish Labour Statistics Office, the average salary of a journalist in Spain is €22,000 per year.

An additional problem is that many journalists fall into the category of “false autónomo”, i.e. freelancers with VAT numbers who are used to fill positions that would otherwise be permanent.

This allows many newspapers to hire without hiring.

According to the Public Employment Service (SEPE), between September 2022 and 2023, there was a six to 14 percent increase in false freelancers compared to 2022.

In Cuardernos de Periodistas, a specialised newspaper, Cristina Puerta wrote in 2022 that in Spain there are more than 73,500 people registered as freelancers. Puerta cites a Madrid Press Association (APM) report, according to which 69 percent of self-employed journalists adopt this status out of necessity, not choice.

“Job insecurity is the major characteristic of media workers in Spain. Since the economic crisis of 2008, journalists, camera operators, photographers and technical staff working for news services have lost between 25 percent and 30 percent of their purchasing power," said Ana Martínez of the Spanish trade union CCOO. "Salaries have not increased at the same rate as inflation”.

France, a case apart?

In France, the Observatoire des métiers de la presse, which analyses developments in the profession, publishes a report on the income of journalists based on data from the CCIJP, the body that issues press credentials. The data only includes cardholders.

In 2023, about 70 percent of journalists in France worked on a permanent contract with a gross median salary of €3,650; 23 percent worked as freelancers (pigistes) earning €1,951 gross, and 2.2 percent worked on a fixed-term contract for €2,958 gross.

Remuneration for French freelancers is regulated at €60 per page (i.e. 1,500 characters). But each media outlet then applies its own rates independently.

France's regulated “pige” system provides some structure, but rates are still modest.

A European situation?

A survey published by the World Association of News Publishers in April 2025 shows that 60 percent of the journalists interviewed have experienced burnout, while 62 percent are forced to supplement their income with other types of work to make ends meet.

The survey is based on about 400 interviews across 33 EU countries and in 13 languages, conducted by Taktak Media/DisplayEurope.

“If the news industry continues its transition to a freelance-dominated model, we will need to invest much more in protecting these workers,” comments Jeff Israely, director of Taktak. “The rise of freelance journalism in Europe is a structural shift in the media industry, as shrinking newsroom budgets have forced outlets to rely more on independent journalists”.

* names were changed at the people's request

This article was produced as part of the PULSE project, a European initiative to support cross-border journalistic collaborations. It was first published on Voxeurop.

The data is not always consistent or comparable, given the different contexts of the media organisations that agreed to participate, as well as the different national contexts. This work should therefore be understood as an overview of a general malaise within the profession in Europe, especially among freelance journalists, and opens up the question of a common regulation for the various employment statuses within the profession.

This year, we turn 25 and are looking for 2,500 new supporting members to take their stake in EU democracy. A functioning EU relies on a well-informed public – you.

Author Bio

Francesca Barca is a journalist, editor and translator at Voxeurop, where she focuses on social issues and inequalities.