Feature

Mapping the housing crisis in the Balkans - a plight decades in the making

For the past seven years, Dejana Stosic, a 26-year-old, has been renting in Serbia’s capital after relocating from a small town in the south of the country. Stostic recently found a job with a higher salary as a coordinator at a private company in Belgrade, but the cost of living remains high, and she has no plans to leave her current house share.

“It takes me one-and-a-half hours to get to work, but I cannot afford to move closer to the office, which is situated in one of Belgrade’s pricier neighbourhoods,” she says. “For a few years now, I have been spending more than half of my salary on bills and rent.”

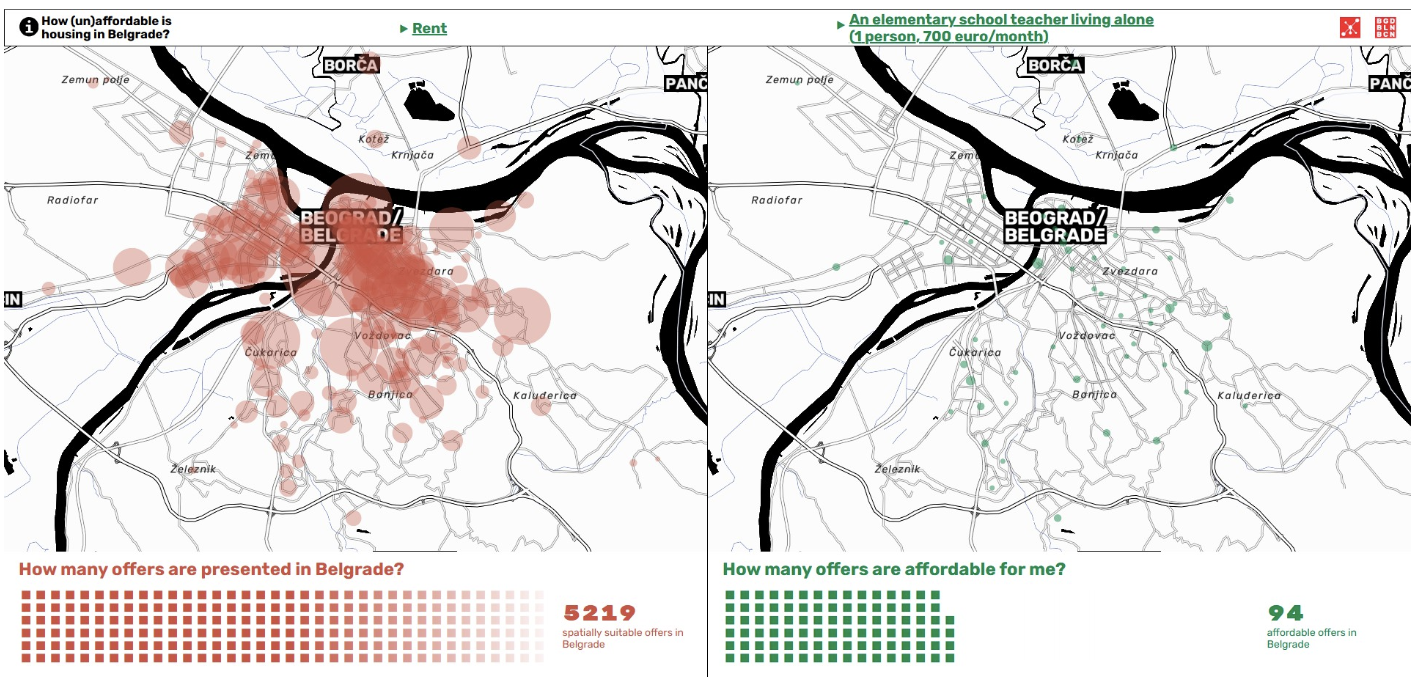

A few years ago, the Ministry of Space, a Belgrade-based NGO specialising in urban development, created an open-source map that collects rental and sale listings in the Belgrade market and compares them to average and median salaries. Stosic’s experience is widely shared — in most parts of Belgrade, the map currently shows red, indicating that housing is far from affordable.

Stosic says she has been dreaming of buying her own apartment for some time.

Recently, the Serbian government launched a loan scheme for people aged 20 to 35 who are purchasing their first property.

While the down payment is only one percent, to qualify, a citizen initially needed to have a long-term contract, while the unemployed needed a guarantor.

After many expressed their dissatisfaction, the Serbian government changed the law in May, allowing people on temporary contracts to also apply under the same conditions as the unemployed, who need a guarantor.

The change means Stosic now qualifies for the scheme, overcoming the obstacle that her lack of a long-term contract once posed.

Currently, renting a one-bedroom flat in central Belgrade can cost anywhere between €600 and €1,200, according to Numbeo — an extensive open-source database offering insights into the cost of living worldwide. In the outskirts of the Serbian capital, prices range from €300 to €650 for a one-bedroom flat. These figures do not include monthly utility costs.

Eurostat defines affordable housing as housing costs that account for no more than 40 percent of a household’s disposable income. According to Marko Aksentijevic from the Ministry of Space, this includes the cost of rent or mortgage and monthly bills.

The average salary in December 2024 was €837, according to the statistical office of Serbia. However, many workers earn less. A more accurate reflection of typical income is the median salary — the midpoint in salary distribution — a stat that illustrates average earnings and highlights income inequality. In December 2024, Serbia’s median salary was €677.60.

“This means that a family of three, with two median incomes in Belgrade, can pay up to €400 for rent and bills without it being a financial burden,” says Aksentijevic. However, the flats currently advertised at that price or lower in Serbia’s capital are “mostly studios,” he adds. “They have to choose between squeezing into a small space or paying more than they can afford. The situation is alarming.”

Aksentijevic explains that most people working in the civil sector, education, and service industries, where salaries are often below average, cannot afford to live near their workplaces.

The Covid-19 pandemic, followed by the war in Ukraine, has significantly increased the cost of living and intensified Europe’s ongoing housing crisis.

“Rental prices in Belgrade soared in 2022, increasing by up to 50 percent in less than a year. The surge was largely driven by the arrival of thousands of Russian citizens fleeing their country after Russia invaded Ukraine more than three years ago,” City Expert, one of Serbia’s largest real estate agencies, told K2.0.

Following that abrupt spike, prices gradually declined over the next two years: they fell by approximately 20 percent in 2023 and a further 10 percent in 2024.

With both house prices and rents on the rise, housing has become an increasing financial burden across the Western Balkans, a region that has seen some of the sharpest price hikes in Europe over the past five years.

In cities like Belgrade, Tirana, and Pristina, the combined cost of rent and utilities is approaching, or even exceeding, average monthly salaries.

The growing gap between supply and demand continues to push real estate and rental prices higher, making housing increasingly unaffordable, particularly for young people and those in vulnerable socio-economic groups.

Kosovo citizens move to unaffordable urban areas

Last year marked a milestone in Kosovo’s urban development. For the first time, just over half of the population lives in urban areas, compared to 38 percent in 2011, according to UN data, the United Nations programme for human settlements and sustainable urban development.

“This represents a major shift toward urban living and reflects broader socio-economic changes taking place across the country,” Besnike Koçani, a spatial and urban planning advisor from UN-Habitat.

The 1998-1999 war in Kosovo had a significant impact on housing availability. According to Kocani, 40 percent of houses were destroyed or severely damaged. In response, much of the rural population moved to cities in search of shelter.

“As a result, the housing landscape experienced a significant rise in informal construction, particularly during the early 2000s. This occurred mainly due to weak institutional oversight and insufficient spatial planning,” adds Koçani.

Kosovo’s urban areas became denser, dominated by multi-residential buildings that were often developed without consideration for infrastructure capacity or urban planning regulations. This has led to uncontrolled urban sprawl, growing pressure on public services, and deepening development disparities between municipalities.

Some areas, especially Pristina, have experienced another construction boom in recent years.

This rise in vacancy rates is closely tied to Kosovo’s large diaspora, with hundreds of thousands of citizens living and working abroad, particularly in western Europe. Many members of the diaspora invest in real estate in their hometowns as a future retirement plan, a form of financial security, or to contribute to their family’s legacy.

However, these properties often remain unoccupied for most of the year, as their owners return only during holidays or summer visits. While this type of investment boosts construction activity, it also distorts the housing market by reducing the supply of available housing, contributing to inflated property values.

In Pristina, renting a one-bedroom apartment costs between €225 for properties on the outskirts and over €300 for those in the city centre, according to Numbeo.

Real estate listings on the websites of rental agencies such as Re/Max Kosova and Infinity Property show that one-bedroom flats advertised for under €300 euros are nearly non-existent. A three-bedroom apartment typically rents for over €300 outside the city centre and more than €600 in central areas.

A person earning an average salary in Kosovo would need to work for two full months, without spending anything else, just to afford one square meter of property

There is no official data on how much real estate prices in Kosovo have increased in recent years. “My estimate is that the increase over the past years was between 20 and 30 percent,” said Driton Tafallari, housing and urban development expert.

Having analysed trends in average salaries and property prices, Tafallari explains that a person earning an average salary in Kosovo would need to work for two full months, without spending anything else, just to afford one square metre of property.

“That is almost double the time that an EU citizen has to work to afford buying one square metre,” Tallafari added.

Even without official data, it is evident that real estate prices in Kosovo have sharply increased. In 2014, a 64 square metre apartment on “Rruga B” was purchased for €720 per square metre. Today, the average price in the same neighbourhood exceeds €1,300 per square metre.

While housing availability in Kosovo has improved, affordability remains a major concern, and it is not the only one. Koçani notes that infrastructure deficits are widespread in both formal and informal settlements, including problems with water supply, sewage, energy, and transportation.

Among countries in the region, Kosovo reports the lowest average salary, with earnings significantly below regional standards. The most recent official data, from December 2024, shows an average net salary of €552. Albania ranks between Belgrade and Pristina in income levels, with average monthly earnings about 30 percent lower than in Serbia and 37 percent higher than in Kosovo.

Living with parents, by necessity, not choice

Albania is facing a similar housing crisis, with soaring rents and stagnant wages making independent living increasingly out of reach for many young people. Despite ongoing construction and rapid urban development, affordability remains a key barrier, especially in the capital.

For Emre Berisha, a 25-year-old taxi driver from Tirana, that means living with his parents in their family home, just like 70 percent of young Albanians. While driving past Tirana’s colorful facades, he shares his grim perspective. “I do not see how I will ever afford to move out — my salary would need to almost double for me to be able to afford it,” says Berisha.

Renting a one-bedroom apartment in Tirana can cost between €500 and €900 a month, while renting a similar unit outside the central parts of the capital ranges from €350 to €500. These prices, which do not include monthly utility bills, already far exceed the 40 percent threshold of monthly income used to define affordable housing.

'In theory, the only way out of living with my parents is getting married and securing a bank loan,' says Berisha

Tirana, Pristina, and Belgrade are the economic centres of their respective countries, attracting large numbers of young people who move there to study and pursue job opportunities.

Unlike Berisha, many of them do not have family housing in these urban hubs and are forced to rent. “Not owning an apartment combined with high prices makes it very difficult for them to live,” said Teuta Nunaj-Kortoçi, an economist from Albania.

“In theory, the only way out of living with my parents is getting married and securing a bank loan,” said Berisha, referring to the burden a bank loan places on an individual, a burden that is more easily shared between two people.

Beyond conventional bank loans, Berisha also has limited chances of benefiting from Albania’s soft loan scheme for young married couples.

Launched in 2018 and revised in 2020, the scheme has continued to focus exclusively on supporting couples, but it has faced widespread criticism for being inefficient and inadequate in scope. In 2025, the City of Tirana supported around 1,200 couples in accessing social housing. To qualify, families must prove they do not own a home or that their current housing falls below minimum standards.

Demand for the scheme far exceeds its capacity. Between 2018 and 2022, only 2,652 out of 7,645 applications were approved — less than half, according to official data.

In Belgrade, Stoisic has a similar experience. “Buying property still seems like a mission impossible – maybe if I get married and have children, I could secure a loan for couples,” Stoisic says.

In Serbia, the parliament recently adopted amendments to the law on subsidised loan schemes for citizens aged between 20 and 35.

Irrespective of employment status, first-property buyers can apply for up to €100,000 of state-subsidised loans. The minimum deposit is only one percent, and the mortgage repayment can take up to 40 years. After the law was adopted, there were several thousand applicants. As such, the scheme was criticized by some economic experts as unsustainable.

There are two other types of housing loans available for couples struggling to buy property, both aimed at underdeveloped towns and villages.

In 2021, the ministry of rural welfare launched a small grant scheme offering €10,000 to families wishing to purchase houses in rural areas. The opportunity is open to people under 45, including married or cohabiting couples, single parents, and young farmers. Applicants must be current renters, have a degree in medicine, pharmacy, agriculture, veterinary medicine, or work in crafts, jobs that are compatible with living in the countryside.

In Kosovo, there are currently no housing schemes specifically for young people. However, in December 2024, the Kosovo Assembly passed the Draft Law on Social and Affordable Housing.

The law lays the groundwork for an eight-year national housing strategy and proposes the creation of a Housing Agency to oversee and centralise implementation. It introduces affordable housing initiatives, including subsidies for apartment purchases targeting young people among 17 identified groups.

The law also extends social housing benefits to those unable to afford market-priced housing, capping rent at 30 percent of a family’s income. Young people have been newly included as a target category, though the law does not yet outline concrete measures for them.

Can social housing provide a solution?

In western Europe, social housing is intended not only for low-income families but also for citizens earning a living wage — as a way to help them enter the property market — the situation is quite different in Serbia, Kosovo, and Albania.

Despite a growing number of people struggling with housing affordability, the limited social housing available in these countries is reserved almost exclusively for the most vulnerable groups. Even then, long waiting lists remain.

In Albania, social housing, both public and private, accounts for only 0.1 percent of the total residential stock, according to a 2014 report by the UN Economic Commission for Europe.

In Serbia, the state owns just 0.5 percent of the real estate market, offering these units for rent or sale at subsidized prices.

As in Albania and Serbia, social housing in Kosovo is intended to support economically and socially vulnerable citizens

In Kosovo, social housing is regulated by municipalities and has not yet been developed into a centralised national program. Since 2003 and up until 2024, most municipalities have built or allocated separate buildings specifically for social housing. According to data from the Ministry of Environment, Spatial Planning and Infrastructure (MESPI), 20 municipalities currently operate social housing programs, all based on the same model — standalone buildings where only beneficiaries of the social housing scheme reside.

The shortage of municipal and social housing is not only a challenge in the Western Balkans but also a growing concern across the European Union.

Only eight percent of the available housing stock in the European Union is classified as social housing, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

While no country in the Western Balkans has recorded housing-related protests in recent years, citizens in several EU countries have taken to the streets, demanding government action to address the housing crisis.

This article was produced as part of the PULSE, a European initiative supporting cross-border journalistic cooperation. It was first published on K2.0.

This year, we turn 25 and are looking for 2,500 new supporting members to take their stake in EU democracy. A functioning EU relies on a well-informed public – you.

Author Bio

Jovana Matthews is a journalist based in Belgrade, Serbia.